Interest is a fee paid on borrowed assets. Assets that are sometimes lent with interest include money, shares, consumer goods through hire purchase, major assets such as aircraft, and even entire factories in finance lease arrangements. The interest is calculated upon the value of the assets in the same manner as upon money. Interest can be thought of as "rent on money". For example, if you want to borrow money from the bank, there is a certain rate you have to pay according to how much you want loaned to you.

Interest is compensation to the lender for foregoing other useful investments that could have been made with the loaned asset. These foregone investments are known as the opportunity cost. Instead of the lender using the assets directly, they are advanced to the borrower. The borrower then enjoys the benefit of using the assets ahead of the effort required to obtain them, while the lender enjoys the benefit of the fee paid by the borrower for the privilege. The amount lent, or the value of the assets lent, is called the principal. This principal value is held by the borrower on credit. Interest is therefore the price of credit, not the price of money as it is commonly believed to be.[citation needed] The percentage of the principal that is paid as a fee (the interest), over a certain period of time, is called the interest rate.

History of interest

Interest is the price paid for the use of savings over a given period of time. In ancient biblical Israel, it was against the Law of Moses to charge interest on private loans.[citation needed]During the Middle Ages, time was considered to be property of God. Therefore, to charge interest was considered to be commerce with God's property. Also, St. Thomas Aquinas, the leading theologian of the Catholic Church, argued that the charging of interest is wrong because it amounts to "double charging", charging for both the thing and the use of the thing. The church regarded this as a sin of usury; nevertheless, this rule was never strictly obeyed and eroded gradually until it disappeared during the industrial revolution.[citation needed]

Usury has always been viewed negatively by the Roman Catholic Church. The Second Lateran Council condemned any repayment of a debt with more money than was originally loaned, the Council of Vienna explicitly prohibited usury and declared any legislation tolerant of usury to be heretical, and the first scholastics reproved the charging of interest. In the medieval economy, loans were entirely a consequence of necessity (bad harvests, fire in a workplace) and, under those conditions, it was considered morally reproachable to charge interest.[citation needed]

Interest has often been looked down upon in Islamic civilization as well for the same reason for which usury was forbidden by the Catholic Church, with most scholars agreeing that the Qur'an explicitly forbids charging interest. Medieval jurists therefore developed several financial instruments to encourage responsible lending. These instruments sometimes closely resemble interest, leading some to wonder whether they truly satisfy the letter and spirit of the rule.[citation needed]

In the Renaissance era, greater mobility of people facilitated an increase in commerce and the appearance of appropriate conditions for entrepreneurs to start new, lucrative businesses. Given that borrowed money was no longer strictly for consumption but for production as well, interest was no longer viewed in the same manner. The School of Salamanca elaborated on various reasons that justified the charging of interest: the person who received a loan benefited, and one could consider interest as a premium paid for the risk taken by the loaning party. There was also the question of opportunity cost, in that the loaning party lost other possibilities of using the loaned money. Finally and perhaps most originally was the consideration of money itself as merchandise, and the use of one's money as something for which one should receive a benefit in the form of interest. Martín de Azpilcueta also considered the effect of time. Other things being equal, one would prefer to receive a given good now rather than in the future. This preference indicates greater value. Interest, under this theory, is the payment for the time the loaning individual is deprived of the money.

Economically, the interest rate is the cost of capital and is subject to the laws of supply and demand of the money supply. The first attempt to control interest rates through manipulation of the money supply was made by the French Central Bank in 1847.

The first formal studies of interest rates and their impact on society were conducted by Adam Smith, Jeremy Bentham and Mirabeau during the birth of classic economic thought.[citation needed] In the early 20th century, Irving Fisher made a major breakthrough in the economic analysis of interest rates by distinguishing nominal interest from real interest. Several perspectives on the nature and impact of interest rates have arisen since then. Among academics, the more modern views of John Maynard Keynes and Milton Friedman are widely accepted.[citation needed]

The latter half of the 20th century saw the rise of interest-free Islamic banking and finance, a movement which attempts to apply religious law developed in the medieval period to the modern economy. Some entire countries, including Iran, Sudan, and Pakistan, have taken steps to eradicate interest from their financial systems entirely.[citation needed] Interest is the fee to use the money.

Types of interest

Simple interest

Simple interest is calculated only on the principal amount, or on that portion of the principal amount which remains unpaid.

The amount of simple interest is calculated according to the following formula:

where r is the period interest rate (I/m), B0 the initial balance and m the number of time periods elapsed.

To calculate the period interest rate r, one divides the interest rate I by the number of periods m.

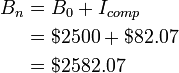

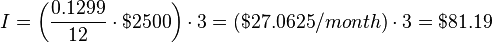

For example, imagine that a credit card holder has an outstanding balance of $2500 and that the simple interest rate is 12.99% per annum. The interest added at the end of 3 months would be,

and he would have to pay $2581.19 to pay off the balance at this point.

If instead he makes interest-only payments for each of those 3 months at the period rate r, the amount of interest paid would be,

His balance at the end of 3 months would still be $2500.

In this case, the time value of money is not factored in. The steady payments have an additional cost that needs to be considered when comparing loans. For example, given a $100 principal:

- Credit card debt where $1/day is charged: 1/100 = 1%/day = 7%/week = 365%/year.

- Corporate bond where the first $3 are due after six months, and the second $3 are due at the year's end: (3+3)/100 = 6%/year.

- Certificate of deposit (GIC) where $6 is paid at the year's end: 6/100 = 6%/year.

There are two complications involved when comparing different simple interest bearing offers.

- When rates are the same but the periods are different a direct comparison is inaccurate because of the time value of money. Paying $3 every six months costs more than $6 paid at year end so, the 6% bond cannot be 'equated' to the 6% GIC.

- When interest is due, but not paid, does it remain 'interest payable', like the bond's $3 payment after six months or, will it be added to the balance due? In the latter case it is no longer simple interest, but compound interest.

A bank account offering only simple interest and from which money can freely be withdrawn is unlikely, since withdrawing money and immediately depositing it again would be advantageous.

Compound interest

-

Compound interest is very similar to simple interest; however, with time, the difference becomes considerably larger. This difference is because unpaid interest is added to the balance due. Put another way, the borrower is charged interest on previous interest. Assuming that no part of the principal or subsequent interest has been paid, the debt is calculated by the following formulas:

![\begin{align} &I_{comp}=B_0\cdot\big[\left(1+r\right)^n-1\big]\\ &B_n=B_0+I_{comp} \end{align}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/4/e/7/4e7b10f4c70d9264d80f7c66bfbf640f.png)

where Icomp is the compound interest, B0 the initial balance, Bn the balance after n periods (where n is not necessarily an integer) and r the period rate.

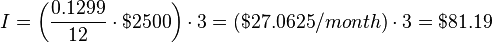

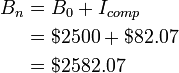

For example, if the credit card holder above chose not to make any payments, the interest would accumulate

![\begin{align} &\mbox{Calculation for Compound Interest}:\\ I_{comp}&=$2500\cdot\bigg[\bigg(1+\frac{0.1299}{12}\bigg)^3-1\bigg]\\ &=$2500\cdot\left(1.010825^3-1\right)\\ &=$82.07\\ \end{align}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/2/e/2/2e29e6081dd8697e4d5cdf34f5586e26.png)

So, at the end of 3 months the credit card holder's balance would be $2582.07 and he would now have to pay $82.07 to get it down to the initial balance. Simple interest is approximately the same as compound interest over short periods of time, so frequent payments are the best (least expensive) payment strategy.

A problem with compound interest is that the resulting obligation can be difficult to interpret. To simplify this problem, a common convention in economics is to disclose the interest rate as though the term were one year, with annual compounding, yielding the effective interest rate. However, interest rates in lending are often quoted as nominal interest rates (i.e., compounding interest uncorrected for the frequency of compounding).[citation needed]

Loans often include various non-interest charges and fees. One example are points on a mortgage loan in the United States. When such fees are present, lenders are regularly required to provide information on the 'true' cost of finance, often expressed as an annual percentage rate (APR). The APR attempts to express the total cost of a loan as an interest rate after including the additional fees and expenses, although details may vary by jurisdiction.

In economics, continuous compounding is often used due to its particular mathematical properties.[citation needed]

Fixed and floating rates

Commercial loans generally use simple interest, but they may not always have a single interest rate over the life of the loan. Loans for which the interest rate does not change are referred to as fixed rate loans. Loans may also have a changeable rate over the life of the loan based on some reference rate (such as LIBOR and EURIBOR), usually plus (or minus) a fixed margin. These are known as floating rate, variable rate or adjustable rate loans.

Combinations of fixed-rate and floating-rate loans are possible and frequently used. Loans may also have different interest rates applied over the life of the loan, where the changes to the interest rate are governed by specific criteria other than an underlying interest rate. An example would be a loan that uses specific periods of time to dictate specific changes in the rate, such as a rate of 5% in the first year, 6% in the second, and 7% in the third.[citation needed]

Composition of interest rates

In economics, interest is considered the price of credit, therefore, it is also subject to distortions due to inflation. The nominal interest rate, which refers to the price before adjustment to inflation, is the one visible to the consumer (i.e., the interest tagged in a loan contract, credit card statement, etc). Nominal interest is composed of the real interest rate plus inflation, among other factors. A simple formula for the nominal interest is:

i = r + π

Where i is the nominal interest, r is the real interest and π is inflation.

This formula attempts to measure the value of the interest in units of stable purchasing power. However, if this statement was true, it would imply at least two misconceptions. First, that all interest rates within an area that shares the same inflation (i.e. the same country) should be the same. Second, that the lender knows the inflation for the period of time that he/she is going to lend the money.

One reason behind the difference between the interest that yields a Treasury bond and the interest that yields a Mortgage loan is the risk that the lender takes from lending money to an economic agent. In this particular case, a government is more likely to pay than a private citizen. Therefore, the interest rate charged to a private citizen is larger than the rate charged to the government.

To take into account the information asymmetry aforementioned, both the value of inflation and the real price of money is changed to their expected values resulting in the following equation:

it = r(t + 1) + π(t + 1) + σ

Where it is the nominal interest at the time of the loan, r(t + 1) is the real interest expected over the period of the loan, π(t + 1) is the inflation expected over the period of the loan and σ is the representative value for the risk engaged in the operation.

![\begin{align} &I_{comp}=B_0\cdot\big[\left(1+r\right)^n-1\big]\\ &B_n=B_0+I_{comp} \end{align}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/4/e/7/4e7b10f4c70d9264d80f7c66bfbf640f.png)

![\begin{align} &\mbox{Calculation for Compound Interest}:\\ I_{comp}&=$2500\cdot\bigg[\bigg(1+\frac{0.1299}{12}\bigg)^3-1\bigg]\\ &=$2500\cdot\left(1.010825^3-1\right)\\ &=$82.07\\ \end{align}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/2/e/2/2e29e6081dd8697e4d5cdf34f5586e26.png)